December 24

Epilogue

„Have ye read this yet?“ a man in a work uniform asked his colleague. The latter tossed the shop assistant a coin and reached for his own copy of the daily newspaper. „I’ve ainlie just seen th‘ headline,“ he replied, „but ah ament surprised. They’re all crooks, these braw gentlemen.“ They walked away chatting, while other customers crowded around the little house with the front pages of the latest editions pasted in the windows. „Edinburgh’s Aristocracy Shaken“ was the headline in the Scottish edition of The Times, the editor-in-chief of The Scotsman had opted for „List of Shame Published: Lost Children Testify to High Society’s Dark Secret“ and Town Topics advertised in the usual style with the words „Stolen Innocence“.

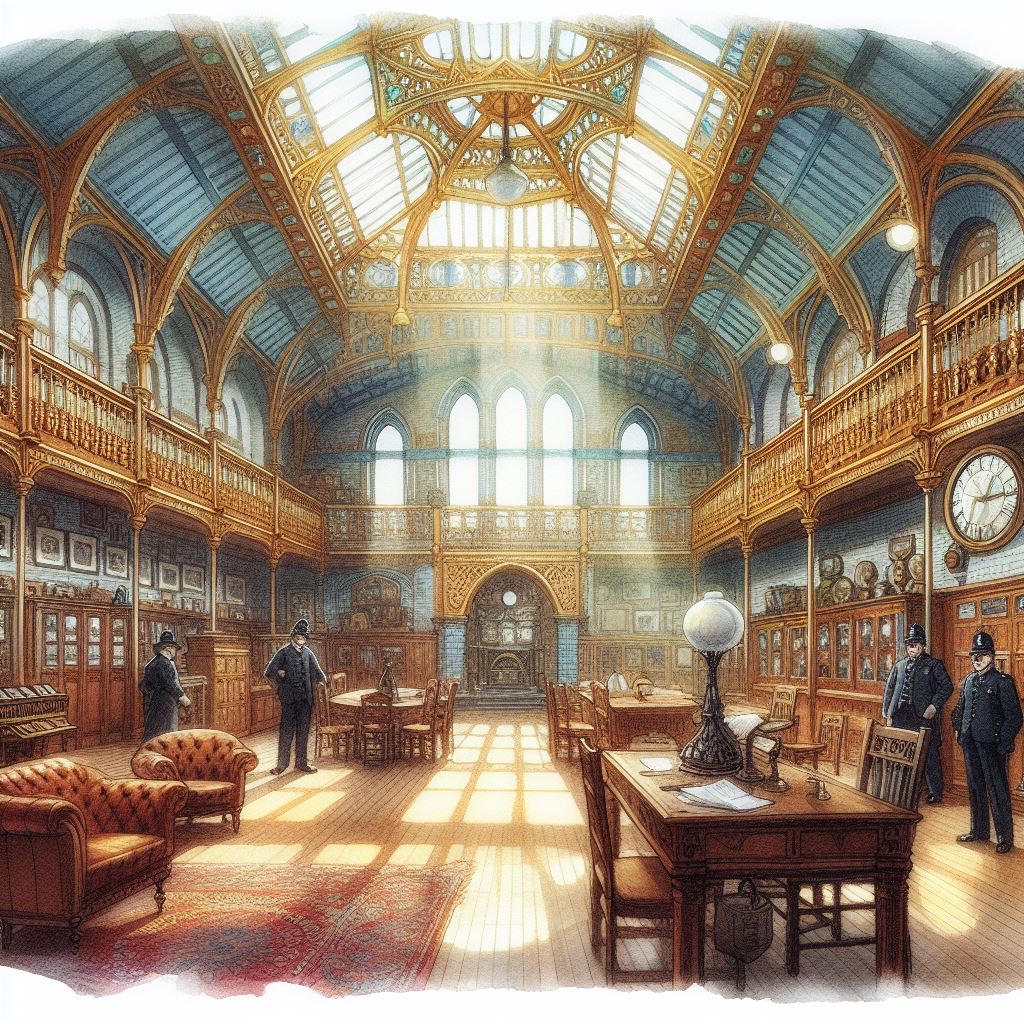

A few streets away, Sir Colin Wentworth was rudely interrupted from his mid-morning breakfast. His butler had rushed into the parlour with flushed cheeks and told him in a whisper that some members of the police were at the door and requested that he accompany them to the station. They weren’t even asking him politely, they demanded him – him, loyal taxpayer and eighth baronet of a lineage stretching back to the 1600s. Let them come! Angrily, he decapitated a boiled egg with the sharp edge of his knife and flecks of yellow yolk splattered across the clean tablecloth. Just then the door to the dining room was pushed open with a sweep and several police officers in blue overcoats burst in. Some in the back rows were already holding their truncheons. What an affront! Wentworth stood up. „Gentlemen, what is this early morning riot about? I must ask you to follow protocol!“ The group parted and a man with a large moustache and bowler hat strode through the cleared passage towards him. „Good morning, Sir Colin,“ he said, and the directness of his address felt like a slap in the face – to the baronet. „I’m afraid I can’t allow you to continue your breakfast in peace. We have an important conversation to have at the police station.“ Wentworth choked and coughed, then downed his coffee, struggling for composure. „Whoever you are, you must believe you’re really doing something here!“ he then gasped. „I’m a Detective Officer with the First Police Department of the City of Edinburgh,“ the other returned, „and like the majority of my police colleagues, I’ve become less of a believer and more of a knower. I still have a few visits to make today – so if you would kindly follow me please?”

A woman stood in front of the castle-like building of Calton Prison. A light snowfall had set in and flakes soon covered the shoulders of her burgundy winter coat. She could see into the courtyard through the open gate and watched the arriving carriages attentively. A number of big names from Edinburgh’s high society arrived at the facility one after the other: politicians, civil servants, members of the lower nobility, entrepreneurs and wealthy private retirees. A smile flitted across the woman’s face as Sir Richard Douglas, a member of the influential Clan Douglas, was led through the yard in handcuffs. It was then that a man came to her side, dressed in a plum-coloured coat, blue striped plum trousers, a scarlet scarf and a matching velvet top hat. „Shocking how some noble men have their masks torn off their faces,“ he said.

She gave him a sharp look. „How nice it would be if that applied not just to some, but to all the noble men of the city.“ He laughed. „If you are referring to me, dear Genevieve – if that even is your real name – you are making the mistaken assumption that I am a noble man.“ „Indeed,“ she replied, „but I would be interested to know the fine detail of how you managed to stand here beside me, Sir Alastair, free and unsullied. After all, you were involved in the Concordia Club. To be precise, you were directly involved in the distribution of the orphan boys, by all accounts.“ Alastair Wallace shrugged his shoulders. „Well, the police could lock me up for that involvement, of course. However, they would lose a valuable key witness. Fortunately, I was one of the first people in our club to be sought out, which gave me a unique opportunity to offer myself as an informant.“ „For which you can certainly expect some mitigation,“ she returned sombrely. He laughed jovially. „Dear friend, it has been a pleasure to go part of the way with you. But now I must return to work. A city hopes and longs for a strong hand to guide it into the unknown of a new century. I want to be prepared for this.“ He tapped the brim of his hat with the index finger of his white-gloved hand. „Think of me at the next election!“ With that, he walked away.

Some days later, in the old pub The World’s End a man and a boy were having lunch. In front of them were meat pies and two glasses of lemonade. They looked up from their meals when an elegantly dressed woman joined them at the table. „Nice of you to come, Miss Fairchild,“ said Ewan Cunningham. „I’m here because I still owe you an apology,“ said Josephine. The reporter leaned back and crossed his arms in front of his chest. „Then let’s hear it.“ She glared at him. „It’s not for you. In the meantime, you’re welcome to go to the bar and get me a glass of wine.“ With that, she pressed a coin into his hand and remained silent until the man sighed – „Right, I’ll be right back“.

William gave her a look and said with his mouth full: „I’m sorry, but I’m so hungry.“ „I understand – and as I said, I’m the one who needs to apologise,“ Josephine returned. „You’ve always been a loyal helper to me and when you asked me to stop working at the Douglases, I didn’t listen to you. That wasn’t right of me.“ The boy wiped his mouth with his jacket sleeve and took a sip of lemonade. „That’s all right, Miss Fairchild. But maybe you’ll give me a few simple jobs in the near future where I don’t get dragged away in broad daylight by some hoodlums in a carriage to be abducted.“ When she remained silent, he leaned forward. „What is wrong?“ Josephine’s gaze had wandered out of the window, a thoughtful crease dug between her eyebrows. „That’s the other reason I came,“ she then said. „I don’t know if I’ll even have any more jobs for you. The police and my contacts at the newspapers have learnt who I am.”

„Well, is it really that terrible?“ said the reporter, who sat back down with them and placed the requested wine in front of her. Josephine sighed and took a sip of wine before answering. „Yes, that’s really terrible, Mr Cunningham. My entire business is based on my anonymity. But now that I’ve stepped out of the shadows, I doubt I can continue to move as freely in high society as I have in the past.“ „I understood that,“ Ewan replied, „but I meant whether it would be so bad if you had to switch your business from scandals and exposés to something more honourable? As a neighbourhood secret club used to say: ‚Nothing happens without a reason‘.” Josephine started, fell silent and paused to think. Then her usual winning smile returned to her face: „Whatever I do, you’ll be the first to know.” William stood up. „Thank you so much for inviting me to lunch, Mr Cunningham,“ he said. “ Sorry I have to go, I have an appointment with Tommy. We’re off to see how they put up the Christmas tree outside St Giles. It was nice to see you, Miss Fairchild. Just let me know if you need me.”

„So we’ve actually cleared it up,“ Josephine said after William had left. „The boys are free, a lot of powerful men are in Calton Prison awaiting trial and one can read about the dealings of the Concordia Club on every newspaper stand in the city. This hidden society will have to invest heavily in its secrecy in order to regain its former strength.“ Ewan nodded. „I never thought I’d say this, but it wouldn’t have been possible without you.“ She sipped her wine and looked at him thoughtfully. „Are we going back to our well-practised antipathy now? Or do you still want to hear me justify the Malcolm Murray case first – that dog who cheated me out of several hundred pounds while I was actually paying him to keep my books?“ „No,“ Ewan said slowly, „it’s good to know, but in the last few days you’ve certainly proved that you do have a heart.“ Then he finished his lemonade and took her arm. „Drink up, Miss Fairchild – shall we see how this tree is put up?”

December 23

Josephine

Detective Officer Ruaridh MacKay stuffed his pipe, lit it and puffed little blue-grey clouds into the air. During this ritual, he kept his eyes on the two people sitting on the other side of his desk. Then he leaned forwards, took a deep drag and said in his sonorous voice: „With all due respect – are you two taking the piss?”

Josephine looked at the reporter sitting next to her. „I’m of the opinion that everyone’s time is too precious for that,“ she replied, „but of course we may as well leave if the honourable gentlemen of the police consider this a trifle.“ She adjusted her hat and stood up in an elegant gesture. „It’s not as if we’ve come empty-handed,“ Ewan Cunningham added quickly, touching her on the arm as if to persuade her to stay without saying a word. „It’s all right, sit back down, Madame,“ McKay grumbled, „you’ll have to excuse my harsh outburst. Not every day someone walks into our station and accuses a handful of the highest members of Edinburgh society of kidnapping, sabotage and a few other serious crimes.” Turning to Ewan, he said: „Then show me what you’ve got there, Mister Journalist. Unfortunately, no one has yet told me in what capacity I may address your companion.“ Josephine took her seat again and brushed a few imaginary specks of dust off the upholstery. „The function of ‚companion‘ is perfectly adequate and sufficient,“ she said, „but you are welcome to imagine our relationship as being more professional and collegial than romantic.“ The policeman laughed. „Don’t worry Madame – policemen have a rather limited imagination. I work purely on the basis of logic and reason.“ „How nice,“ smiled Josephine, „the same goes for me.”

Ewan had placed the black notebook on the table and pushed it over with his fingertips so that it came to rest in front of the older man. „We found it in a secret room in Sir Richard Douglas’s house. Together with the other clues and pieces of information we’ve gathered, it should give you the big picture.“ Ruaridh MacKay stuck his pipe in the corner of his mouth, opened the first page, read and puffed. During the minutes of silence in which he studied the pages attentively, his bushy eyebrows drew together more and more in the centre of his forehead. From time to time he would utter a mumbled „Ah!“ or „Well, look there“ as he read. When he had finished, he closed the notebook and gazed out of the window for a long, thoughtful moment.

Then he turned to his visitors. „Let me try to summarise what this -“ he stabbed the black cover with his index finger as if he wanted to pierce it – „reveals. There is a secret society in Edinburgh that has been operating in secret for decades and is primarily concerned with increasing its own wealth.“ „They call themselves the Concordia Club,“ Josephine added, „and Sir Richard Douglas is its chairman.“ MacKay nodded and continued: „In addition to side agreements, black deals and corruption, this organisation has recently taken to infiltrating young men into certain positions and using them to their advantage.“ „After they’ve kidnapped the boys, they find out where their strengths lie and train them further,“ Ewan interjected. „For example, if one of them is a good waiter, he’ll be deployed at hospitality events to eavesdrop on private conversations. If one is skilful at the machine, he spies on trade secrets at a competitor. The others are used as henchmen, thugs and thieves. The booklet lists all the businesses, economies and even several private households where the club has used its puppets.“ Ewan opened the book again and pointed to the lists: „And each entry states the purpose of the mission – that is, the target person or the task to be fulfilled.”

The detective nodded, then tapped the burnt contents of his pipe into the ashtray. „Very well, thank you for the information. I’ll now take whatever further steps are necessary and put competent officers on the case.“ Josephine looked at him indignantly. „What does that mean? A couple of helmet-wearing monkeys take over and we’re supposed to wait and enjoy a cup of tea?“ „Yes, that’s what it means,“ MacKay said and winked at her. „Nothing more to discuss for now.“ Anger rose in Josephine. “ I beg you pardon, but are the police even equipped to bring such an operation to a successful conclusion?“ she asked with a cutting undertone. „Aye!“ MacKay replied roughly. „If you’re convinced of that, there’s certainly one thing that will interest you,“ she replied. In a cat-like movement, she snatched the notebook from his hand and leafed through it, looking for a page. „Have you read this?“ She threw it open in front of him and looked at him challengingly.

Ruaridh MacKay leant forward and studied the writing closely. Suddenly his eyes widened. „This can’t be true! Tulloch has been with us for several months and has always been exemplary …“ He fell silent and looked into Josephine’s smug face. “ All right, Madame – another point for you. There’s a certain risk involved in cleaning out this Augean stable when we can’t even be sure that our opponents aren’t standing shoulder to shoulder with us.“ „That’s exactly what we were thinking,“ Ewan interjected, „hence we have an idea.“ MacKay sighed. „I never thought I’d say this to ordinary folk: so what’s our plan then?“

After the conversation at the police station, Josephine and Ewan set off in opposite directions. Each of them carried a list in their pockets that had to be completed today. It was particularly important to inform those who were still working on the evening editions last so that they didn’t get any funny ideas. Their aim was not to warn anyone. What they had in mind were the papers that would be on every newsstand, in every letterbox and on every breakfast table in the city tomorrow morning.

December 22

Ewan

A biting winter wind tore at his coat as he hurried through Princes Street Gardens and hurriedly climbed the steps to the Scott Monument. Ewan liked coming here – although preferably not in this weather and in the dark. The monument had been completed only a few decades ago, in memory of the great Scottish poet Sir Walter Scott. Even though he had devoured his works, when Ewan saw the pointed tower, he thought primarily of the stonemasons involved in its construction. Those who had worked on the numerous statues and decorations had died from the effect of the dangerous stone dust on their lungs several years after completion. The Scotsman ran the headline that the monument had cost the lives of twenty-three of Edinburgh’s best stonemasons. The statue of the writer himself also gave him food for thought during his regular visits. With a wistful expression, Scott sat enthroned on the pedestal with a manuscript on his lap and his faithful dog Maida by his side looking up at him.

He stopped at the statue and looked over to Old Town, where a sea of thousands of illuminated windows twinkled dimly through the darkness. Suddenly, a shadow detached itself from one of the pillars and approached him. It was a person in a black cloak, face and head covered by a black hood. These scoundrels probably thought they could trick him a third time – but today he came prepared. In one swift movement, Ewan whipped up the walking stick he had concealed behind his back when he arrived and gave the figure a fierce whack with the handle. To his astonishment, he heard no cry of pain, but a very familiar voice.

„Hell’s bells! Are you out of your mind?“ Josephine pulled the hood off her head and rubbed the spot on her shoulder where he had struck her. Completely perplexed, Ewan lowered the stick. „I … didn’t mean to … excuse me…“ he stammered, but by then the woman had already leaned forwards and smacked him firmly in the chest with her fist. „You enjoy that? I know you don’t like me, but you don’t have to get violent!“ Now it was Ewan who spoke with indignation. “ Now you’ve gone too far! Surely I won’t hit you on purpose – but how was I supposed to know that that letter was written by you if you didn’t sign it?“ „And exactly how was I supposed to sign it? With my real name? I prefer as few people as possible to know it.“ „Very well,“ Ewan returned, crossing his arms in front of his chest, „I’m sorry for smacking you. But perhaps you understand that after two assaults on my person, I’ve become cautious.”

Josephine made a gesture of refusal. “ All forgiven,“ she said, „but I don’t intend to hang about in this cold forever, so we’d better get straight to the point. I need your help.“ „Hmm, that phrase sounds familiar,“ Ewan replied a little spitefully, backing away as Josephine lashed out to smack him again. “ This is no time to hold a grudge!“ she snapped at him. “ They tied me up and would have done who knows what else if I hadn’t escaped. But now William has disappeared…“ „William?“ Ewan caught his breath. „Yes, a boy from an orphanage in the Grassmarket. I thought you were researching this orphan thing…“ „William’s disappeared?“ he shouted. „Tell me!“ „How do you know…?“ They both looked at each other, perplexed, and after a few seconds of silence, Ewan began to laugh. „Ah, trusty William! If anyone can be the servant of two masters, it’s you!”

A short time later, they both came clean. Ewan presented the piece of paper on which he had jotted down the words „Nihil Sine Causa“ and Josephine informed him of everything she knew about the Concordia Club. They both told each other about their encounters with unscrupulous henchmen, thugs and kidnappers. When Ewan told him about the attempt on his life, Josephine grabbed his arm, aghast. If the subject wasn’t so serious, he would have been quietly enjoying the indignation of this otherwise cold woman standing in front of him.

„We must have stirred up a can of worms – both in our own way,“ she said when he had finished. „I suppose I have no choice but to work with you. Hopefully I won’t regret it one day if you give in to your antipathy towards me.“ „Miss Fairchild,“ Ewan returned, „by now I’m far too immersed in this matter myself to let our previous differences be my guide. Let’s just keep the peace until we can shed some light on the matter.“ Josephine studied his face cautiously, then nodded and pulled a black notebook from an inside pocket of her coat. „Can you make any use of this?“ she asked, handing it to him. „I got it from the secret room at the club, but I don’t understand what it might be about. It’s full of tables with names and companies listed.”

It was hard to turn the thin pages of the notebook in the icy wind and with gloves on his hands. Ewan tucked his walking stick under his arm and leafed through the lists. Suddenly he looked at Josephine and realization shone from his eyes. „If there’s one key to this mystery,“ he said, „you’ve found it here.”

December 21

Josephine

Tearing open the door of the White Hart Inn, she rushed to the bar and demanded a double whiskey. When the innkeeper didn’t obey quickly enough, she angrily banged her fist on the wooden counter. The drink was placed in front of her, she drained it in one go and threw down the coins for another. Only after she had emptied a third glass did she stand up, swaying slightly. „Wifie, is everything a‘ richt?“ the man behind the counter asked her when he noticed her bewildered look. „Aye“ said Josephine, making a dismissive gesture. Right now, she didn’t want to talk to anyone. She leant on the bar and let her gaze wander around the smoke-filled room with its low, black-painted wooden ceiling. The voices of the other guests blurred into an inseparable murmur. A headache throbbed in her temples, but not just from the whiskey.

The memory of the morning forced its way painfully through the haze of alcohol. A thin winter light had shone through the flimsy curtains of the room where the orphanage director had told her that the boy had been gone for several days. „Have you been looking for him?“ she had asked, and when the woman shook her head and returned a dry „‚Cause how come on earth would I?“ anger had welled up in her stomach like an angry animal. On the way out, she stopped several children, but each confirmed that William had disappeared without notice. As she walked the path from the orphanage back to the Grassmarket, she paid no attention to slush, mud, horse droppings and muck. Beggars and other vagrants approached her, but after she had firmly pushed away the first one who had grabbed her by the sleeve, they left her alone until she reached the old pub.

Josephine left the pub and walked down the street to the east. The whiskey had eased her anger, but it had been followed by a much more unpleasant feeling: Shame. On an impulse she couldn’t explain, she entered St Giles‘. The hall of the church was gloomy and cold. Josephine sat down in the row where she had sat the last time and talked to William. She took a deep breath and looked up at the blue-painted vault that rested high above her on the ornate pillars. „Why do I feel like this?“ she pondered. William had never given her any reason to be unhappy, he was always loyal and kept her secrets as if they were his own. Without him, maybe I and my business wouldn’t exist at all, she thought and then shooed the thought away again – now things were getting melodramatic. That must have been the alcohol talking. „Honestly, I couldn’t care less,“ she scolded herself, but she knew that wasn’t true. The boy had been in the Douglases‘ house on her direct orders, he was scared and she had thought of nothing better than to take advantage of his desperate situation. „As a woman, I should actually know better how to handle power sensibly,“ she thought, a bitter line forming around her mouth.

Josephine let her gaze wander over the church windows, through which a slightly brighter light fell today than on her last visit. Above the depiction of the crucifixion of Jesus was a second row in which the coloured glass showed his ascent into heaven. In contrast to the scene below, it was not dark and hopeless here, but the sun burst forth in yellow glass stones and the disciples looked devoutly at their Lord, who turned his face upwards into the light. Josephine noticed another detail: While only a few around the cross had a halo adorning their heads, all those who stood at his feet during his ascent were illuminated. She remembered so much from Sunday School that not all those who had accompanied him on his last journey were loyal to him – those who remained so after his death were remembered all the more by the faithful. „Who do I want to be?“ a thought flashed through her mind.

She stood up with a jerk, her mind made up. She nodded towards the ascending man encased in stained glass and threw a shilling into the donation box on her way out. All the way through the Old Town, her mind was running at full speed. The city’s haze was particularly thick that afternoon, and the yellowish smoke from the chimneys mingled with a thin mist that made the church spires and rooftops seem distant. The streets were very busy. She had to dodge several stray carriages that rolled dangerously close to the pavement. There were people everywhere who approached her and offered her food, newspapers, political pamphlets or small wares, while war invalids, children and ragged women squatted between them, hoping that their benefactors would be more willing to help them before the holidays. Absent-mindedly, she pressed a coin into the hand of a boy who must have been no more than five years old. He stood in the snow in wooden clogs and shorts, his eyes shining as he held the coin in his small hands. Josephine had already moved on before he could thank her.

When she arrived at her destination, the skinny housemaid she had hoped for and was familiar with from a previous job opened the door. She asked for the master of the house, but he wasn’t there and wouldn’t be home for a few hours. So she left a note, sealed the envelope and made her friend promise not to give it to anyone else and to throw it in the fire in case things turned out any differently. Then she headed home.

An hour before the agreed time, Josephine put on her black coat with the wide hood. Even if you broke new ground, you had to stay true to yourself a little, she thought.

December 20

Ewan

Dusk had already begun to fall by the time Ewan hurried along the country road. Two villages he had already passed through and even though he could read their names on the weathered signs, they seemed completely unfamiliar. Whether he was actually heading towards the town or not was a mystery to him. He couldn’t see a soul far and wide that he could have asked. All he knew was that he had to keep heading east with the water behind him.

Besides the worry of being surprised by nightfall in the middle of the snowy solitude, his thoughts centred on what had happened a few hours ago. The orphans had refused to come with him and what Tommy told him continued to haunt his mind. The pieces of the puzzle wouldn’t fit together in his head. Philip Rowe – a man in extravagant clothes – the selection process – lessons – the „next phase“. Then there was the strange message that had been left for him after the break-in at the office. The whole thing was clearly getting out of hand. All of a sudden, Ewan felt terribly alone. After the robbery, his editor-in-chief had advised him to leave the story behind and take a few days off. Josephine Fairchild, who had been his last hope, had turned him down. Who else could he turn to?

Night slowly descended over the snow-covered fields around him. A dark blue streak crept up on the horizon, growing rapidly and blocking out the last of the daylight. Although he was walking in a rutted gully on the country road, he could already feel the first wet patches on the tips of his boots where the slush was seeping through the leather seams. Another village lay ahead of him and as he approached, he recognised the name on the sign. His heart jumped with joy. He had reached Crewe Toll, the junction between Crewe Road and Ferry Road, which bore the name of the former toll house. All that was left was the old smithy and the reason for Ewan’s euphoria: the Caledonian Railway stop that would take him back to the heart of the town. Ewan had almost reached the platform when he heard the steady sound of an approaching train in the distance. Then the steam locomotive rounded a bend, crowned by a column of smoke. Ewan was relieved to see that it was pulling carriages behind it, painted in crimson and white – the unmistakable sign that they were passenger carriages. He ran the last few metres and reached the train just in time.

Exhausted, he let himself fall into the dark blue velvet cushions. No man could be so lucky, he thought. Trains departed from Crewe Junction in all directions and this particular one would take him to Princes Street in Edinburgh’s New Town. From there it was only a stone’s throw to – well, where was he going anyway? To the office? Home? In his current state of mind, a visit to the pub might be the best option. But he didn’t have to make that decision for the time being; the journey would take at least another half an hour. All at once, Ewan realised how exhausted he was. Sitting opposite him was an elderly lady who had greeted him as he boarded and then returned to her crime novel. He politely asked her to wake him as soon as they reached Princes Street and she happily obliged. Completely drained, he leaned his head into the corner of the seat and as the wintry landscape outside drifted by, his eyes fell shut and the gentle cradle of the train rocked him into a deep sleep.

When he left the train at Princes Street, he felt scattered and the cold night air seemed even more unpleasant than before. There were no pubs on Princes Street, so he turned his steps towards Old Town. With the Royal Scottish Academy on his left and the dark gardens on his right, he soon reached the winding maze of Old Town streets. His hat had got lost in all the confusion, so he combed his hair over his face with his fingers and turned up the collar of his coat so that prying eyes wouldn’t recognise him at first glance. In Candlemaker Row, he headed for the old pub, which he knew still served good food late into the night. As he passed the drinking fountain with a bronze dog sitting on top, he absentmindedly stroked its head. „Bobby“ had guarded his master’s grave in the neighbouring Greyfriars Kirkyard for fourteen years until he himself passed away. Enchanted by the story, one of the richest women in the United Kingdom memorialised the little terrier.

The pub was noisy and crowded, but Ewan found a corner to retreat to with an ale and a large bowl of stew. The soup tasted marvellous and the strong beer gave him exactly the kind of pleasant buzz he had hoped for. His spirits were soon revived and he felt ready to make his way home. Fortunately, his little flat was not far away.

The next day, Ewan didn’t wake up until midday. When he finally got up, he felt a strange clarity. Well, should they all abandon him, beat him up, intimidate and kidnap him – he was a journalist, bloody hell! He would publish this story, whatever the cost. Britain had been the first nation to introduce freedom of the press in 1695 and no less was at stake today, Ewan thought bitterly. Once it had gone to press, he thought, he could contact the police and ask them to escort him in the following days – even if this request already seemed futile. Nevertheless, after a quick breakfast, he made his way to the editorial office with determination.

The acrid smell of smoke permeated the streets just two intersections before the Scotsman’s noble building. Several horse-drawn teams appeared in the distance, pulling fire engines behind them, while members of the Edinburgh Fire Brigade hurried to work in their black jackets, bright trousers and shiny helmets. A chain formed, buckets filled with water were passed from hand to hand to fight the inferno in the shattered windows. Thick smoke had engulfed the entire street and Ewan sought to speak to a policeman standing nearby. „Excuse me, Sir – I work at the Evening News.“ The policeman shrugged his shoulders and replied: „Aye, looks like that’s over for now.“ Undeterred by the laconic reply, Ewan continued, „Do you know how it happened yet?“ “Brigade thinks it was arson,“ said the policeman, „you’d hardly be daft enough to leave an open fire in a newsroom with all that paper around. And electricity hasn’t been installed there yet.”

Ewan thanked him and turned back to the burnt-out house. What had happened seemed like a direct warning to him after he had escaped: „You may have escaped our control, but we can hurt you wherever you are hiding.”

December 19

Josephine

She had been taken to the laundry room of the house and tied to a chair. Her protestations that she had only entered the secret room by mistake were ignored. „She’ll stay here until Sir Richard comes home,“ the young, uniformed man told the cook, „and rest assured – there will be repercussions for you afterwards.“ After they had left her alone, Josephine looked around. Perhaps she could find a way to free herself and escape. The room was narrow and lined with tall linen cupboards at the sides. There was a hand-cranked washtub, but in all likelihood it was only used to clean small items of laundry in an emergency. Like all well-off families, the Douglases used the services of a commercial wash house, of which there were many in the city. At the far end, Josephine recognised a door with glass panels allowing daylight to flood in. If she was lucky, there was an exit to the garden – the idea was not far-fetched, as it was necessary to get to the washing line with fresh laundry as quickly as possible.

But before she could turn her attention to the question of how to get rid of the ties, the door was pushed open and Richard Douglas entered, accompanied by another man. Josephine almost breathed a sigh of relief: it was Alastair Wallace walking alongside Sir Richard. It was good to know him as a silent ally in this situation. If she didn’t let on now and gained a moment alone with Alastair, he would surely set her free. But first Sir Richard addressed her. „Good afternoon, miss,“ he said in a tone as sharp as a judge’s sword. „I am always happy to have guests in my house – but I would like to be the one to show them round. You, on the other hand, have let yourself in and gained access to a room that even most of my servants don’t know exists.“ „I’m truly sorry, Sir,“ she said, putting all the feigned innocence she could muster into her voice, „but I was looking for my earring. I must have lost it at one of your recent evening parties here. I was just looking in the library when the shelf opened to reveal a corridor.“ She breathed heavily and then squeezed out a few fake tears – a skill that had often saved her from dicey situations. „You can judge me for my curiosity – but please, Sir: I don’t deserve such cruel treatment.”

Sir Richard narrowed his eyes and took a few steps towards her. „On the contrary,“ he then said, „I think we’ve been far too gentle with you up till now. What do you say is your good name?“ Josephine’s gaze flew to Alastair, then she made a decision. „Genevieve Stirling,“ she said. Richard Douglas laughed. „Ah, how interesting – and my cook swears you introduced yourself to her as Evelyn Saunders. Fortunately, I know the wife of our Councillor. Even though she rarely appears in public, I am quite certain that she bears no resemblance to you.“ „She must have been mistaken!“ said Josephine in feigned exasperation.

Then Alastair Wallace spoke up. „Well, Saunders and Stirling – the names do sound similar. My dear fellow, perhaps there has been a case of confusion.“ Sir Richard gave him a sideways glance, a frown on his face. „Well, I’ll go and ask the woman. Then I won’t have to be accused of judging people unjustifiably – even if they move about freely in my private chambers as if it were their own home.“ With that, he left the room. Josephine breathed a sigh of relief. „My dearest Alastair!“ she burst out, once she was sure that Douglas was out of earshot. „Please help me – look, I’ve been tied up! It was at the dinner party where we met that I lost my earring! I assure you, it’s all just a terrible misunderstanding.“ But Alastair made no move to untie her and began to walk up and down the room. Then he came to her, squatted on the floor in front of her and studied her face closely. „My dear,“ he said, „you must really think me a very simple-minded man.”

Josephine choked, but didn’t let on. „Excuse me? Not in any way, why would I…?“ He looked at her with pity. „Well, I don’t blame you. Many people only look at my superficial appearance and think of me as nothing more than a conceited dandy who, thanks to his family’s money, indulges in daydreams of times long past. Some people might be offended by this – but I quickly realised that it can be more profitable to be underestimated than overestimated. A mistake that you have obviously also made.“ Josephine slowly began to suspect that he was right. It was probably better if she kept quiet and let him speak until the other man returned. „When we first met, of course, I had no suspicions,“ Alastair continued, „but then you asked me about my goals and ambitions in the botanical gardens a little too calmly. A woman like you knows that men like to talk about such things. I didn’t buy your constant assurances that you were just a simple-minded socialite. I also noticed that while you wanted me to reveal more and more of my true self, you kept the wall around you in place.” Josephine’s heart beat faster, but Wallace didn’t give her time to think clearly. „Well, the final confirmation came this afternoon: what stone did you say you were looking for in an earring?“ „A sapphire,“ she whispered. He grinned. „You claim to have worn blue jewellery – with a green tartan dress? My dear, you can fool any other man with that, but you certainly can’t fool me.”

Now the only option was to move forwards. „Well, I lied,“ she hissed – „I wanted to have a look around this place.“ „For what purpose, my dear?“ She thought about it, then put all her cards on the table. „You told me about the secret club. In fact, I’ve heard about it in other societies and several clues led me to Sir Richard. As I said, it was pure curiosity.“ „Did you find anything in the room?“ „No,“ she said, putting in a hint of regret. „Nothing, I’m afraid. I was also caught a few minutes after I found the secret door.“ Alastair raised an eyebrow, but remained silent. „But Alastair,“ she continued, lowering her voice in case anyone overheard her, „didn’t you tell me you wanted to bring down the club? Perhaps we can work together. Please untie me – then I’ll become your ally in the shadows and once you’ve achieved your goals, we can work together…”

She fell silent as Richard Douglas entered the room. Alastair turned to him. „What did the interrogation reveal, Sir Richard?“ „Nothing we didn’t already know, dear Alastair. My cook swears she heard the name Saunders. What have you found out in the meantime?“ Alastair cleared his throat and Josephine clung to the seat of her chair. „This lady is a fraud,“ he then said. „Not only has she entered your private chambers without permission, she has done so for a purpose. Allow me, Sir Richard, to make a bold assumption: the person who is trying to bring down our Club is sitting in front of us.“ Sir Richard’s eyes widened. „This woman was involved with Murray, you say?“ Alastair nodded. „As you know, you appointed me Chairman of the Commission. I’m all the more pleased to be able to successfully roll this case out before you.”

Now she realised everything. This rotten bastard was trying to climb the career ladder over her dead body. But she still had one last trick up her sleeve that neither of them would expect. She had never done it before, but if there was a favourable moment, it was now. Josephine quickened her breathing, moaned and began to twitch violently. Then she tensed her arms in front of her chest, just as she had seen the man with falling sickness do in the street. The spectacle had the desired effect and from the corner of her eye she could see that both men were staring at her in horror. Josephine increased her convulsions and finally managed to topple the chair. „Staff!“ shouted Sir Richard, casting a disdainful glance at her and hurrying out. Meanwhile, Sir Alastair crouched down on the floor next to her and watched her with a scrutinising gaze. „You think you can catch me,“ Josephine thought, „then take a good look at this.“ She contorted her face into a hideous grimace and began to chatter her teeth so wildly that she foamed at the mouth. Disgusted, Alastair backed away and left the room.

Shortly afterwards, someone was with her and untied her. She struggled to keep twitching, even when they laid her on the floor and clamped a piece of wood between her teeth. „We need a doctor!“ she heard a woman’s voice shout. „No doctor,“ came Sir Richard’s reply from some distance away. „Leave her there until she’s cooled off. Then I’ll give further instructions. Until then, have the boy look after her.”

The boy? Josephine’s heart beat excitedly. Could she really be so lucky? When William entered the room a few moments later, she could have screamed with joy. Fortunately, he didn’t let on and sat down in the chair next to her head. „They’ve all gone,“ he said to her in a whisper a little later. She calmed down immediately, carefully sat up and took the wood out of her mouth. „William! I’ve never been so happy to see your face!“ He smiled. „Let’s get the hell out of here, Miss Fairchild.”

December 18

Ewan

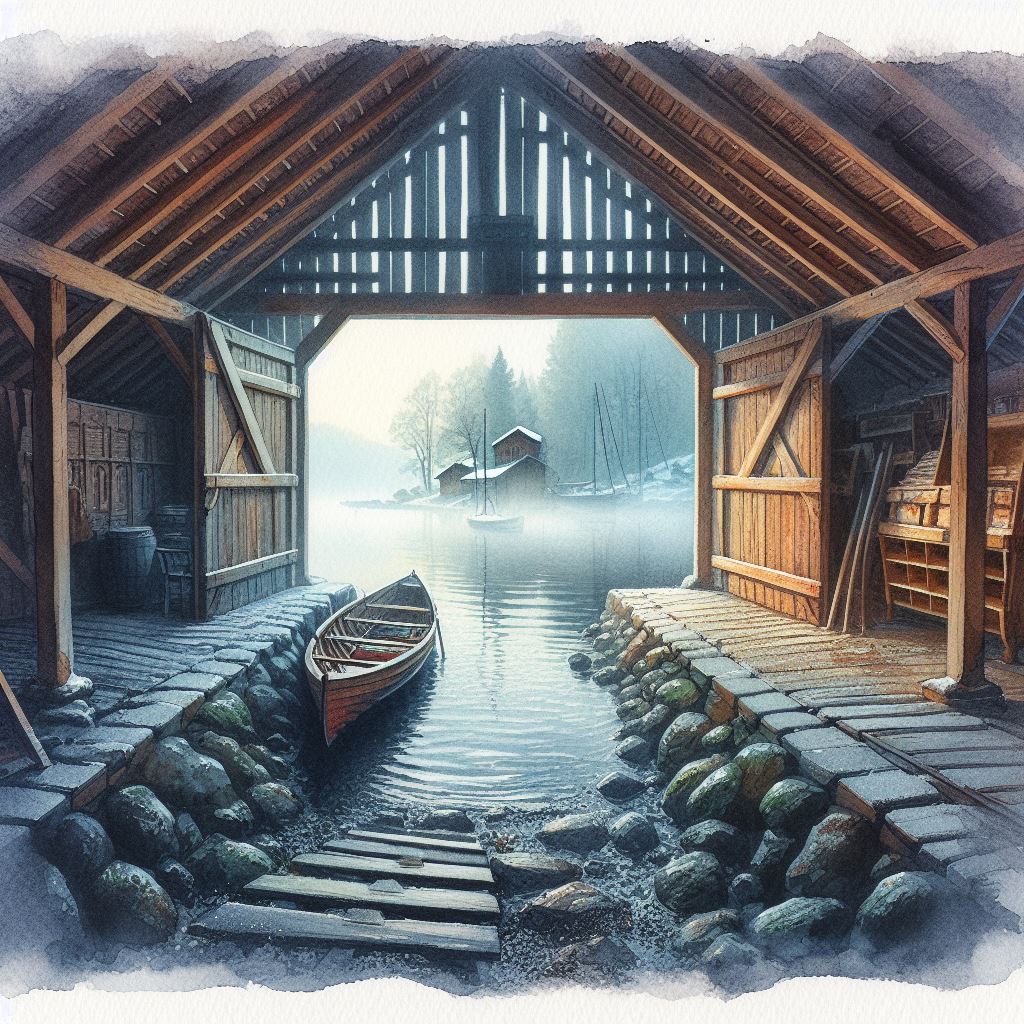

When Ewan woke up, he was freezing. At first he thought it was night because he couldn’t see, but then he remembered. They had put a bag over his head, which still obscured his vision. His hands and feet had also been tied together, which made it considerably more difficult for him to stand up. At first, he could do nothing but lie there helplessly and concentrate on his remaining senses. A breeze and the soft lapping of waves told him that he was out in the open and near water. However, the echo of the sound reverberated briefly, which led him to conclude that some kind of building must be surrounding him. At first he could feel nothing but cold, but then his hands touched hard stone that sloped slightly under his body.

Suddenly he felt something wet on his shoulder. It must have been a wave, because after a short pause the water returned and wetted more of his body. Was he lying right on the edge of a river? He tried to roll away from it, which the steep ground beneath him made practically impossible. A few minutes later, his whole arm was already submerged in cold water. Horrified, a thought flashed through his mind: the tide! He must have been left in a place that was regularly flooded at high tide. In a blind panic, he tried to break his shackles by pushing and kicking, but they only cut more deeply into his skin. Something pressed uncomfortably against his ankle and made Ewan want to scream with happiness. He had completely forgotten about his little pocket knife, which he always kept hidden in his left boot for exactly such emergencies, but he had remembered it at exactly the right moment. It took some contortions to get to the knife and cut the restraints, but finally Ewan freed himself, sat up and pulled the bag off his head.

Now he realized where he was: He was lying on the ramp of a wooden boathouse with its doors open, overlooking a wintry stream. Ewan saw snow-covered trees standing on the riverside, a gentle mist hung over the water, but there was nothing to indicate what time of day it was. Not a soul was to be seen anywhere. Should he dare to call for help? He had obviously been deliberately left there, fully expecting the tide to do the job and drown him. If that was the case, those who had brought him here were not ruthless or brave enough to murder him themselves, he thought, as they had let the forces of nature handle the dirty work. Or perhaps they wanted to cover their tracks.

He struggled to get up, his muscles aching from the unnatural position he had obviously been lying in for several hours, helped by the cold floor. The first thing he did was walk to the gate of the shed, but of course it was locked from outside. He looked around helplessly. Surely there had to be something here that could help him! All the walls were lined with shelves containing tools and materials for care and maintenance, none of which were suitable for breaking down a solid wooden gate. Then Ewan noticed the boat which was moored in the entryway and was increasingly being washed by the incoming tide. He got an idea.

A few minutes later, he rowed out onto the still water. Now he could see that he was on a short channel to the sea, as the Firth of Forth opened up in the distance. The further he got from the boathouse, the better he could see his surroundings. In front of him was an expansive lawn that was part of a large landscaped park with woodland areas, tree-lined avenues and artificial ponds. On the horizon, he could make out the outline of a house, its pointed chimneys poking out of the mist. Ewan maneuvered his barge towards the shore and soon reached land with mostly dry feet. He was already halfway towards the house when reason knocked. What if the people who had overpowered him and left him for dead were right there? At the same time, this was also a golden opportunity to find out who was responsible, he thought. He approached the building cautiously and under the cover of a small wood.

Suddenly he heard the crunching of large wheels on gravel and saw a black carriage rolling out of the yard. Ewan’s heart beat faster. Whoever had been there had obviously just left. If ever there had been a good opportunity, it had just presented itself to him. When the carriage was out of sight, he crept around the house.

The sandstone building resembled a small castle with its stepped towers, artificial embrasures and battlements on the gable. Ewan found the entrance portal under a canopy. He held his breath for a moment – but the door was unlocked. He opened it just a narrow crack and silently entered the heart of the castle. The scent of old wood, musty carpets and faded linen surrounded him as he wandered through the rooms on the lower floor. In one of the rooms he discovered antique furniture and paintings, in another a kitchen with an open fireplace that smelled of cold food. However, he found no clues as to who lived here. After combing through all the halls on the first floor with no results, he found the staircase leading to the second floor. The steps creaked softly under his boots as he climbed them. Once in the upper corridor, he carefully opened a door. Behind it awaited him a dormitory that could have come straight out of a Dickens novel and whose bleak appearance in no way matched the rest of the venerable house. What was even more surprising was that the room was full of people.

About twenty boys of different ages were sitting on the beds. Some of them were reading, others were chatting quietly. When the strange man entered, they raised their heads and there was a look of fear in many eyes. Ewan was taken aback. Could this really be possible? His gaze flew over the faces and lingered on one he knew. „Tommy?“ he asked, puzzled. Thomas Murphy was equally perplexed: „Mr. Cunningham? What are you doing here?“ „I could ask you the same question. What are you doing here? What’s this place all about?“ The red-haired boy put down the book he had been reading and got up from the bed. „Sir, I think it would be better if you got out of here as quickly as possible.“ Ewan shook his head. „I’m sorry, but there’s no way I’m leaving this place until you’ve told me what’s going on.“ Tommy looked around the room questioningly, but the other boys made no move to interrupt. Then he sighed. „Well, Sir, here’s the thing: we’ve all been brought here one by one.

„Fine, but you have to promise to leave afterwards.“ Ewan nodded. „Well, Sir, here’s the thing: we were all brought here one by one. A selection process was carried out shortly after we arrived.“ „What do you mean?“ Ewan interrupted agitatedly. „They wanted to know what we’re good at – who can talk well, who has a clue about technology, who has worked in a fine household before. Then we were sorted and have been receiving lessons in groups ever since.“ „Lessons?“

Tommy nodded. „They say it’s part of the preparation for what they call the ’next phase‘. Unfortunately, no one here knows what that is. Some of us keep getting there and being picked up. None of us have come back yet.“ Ewan couldn’t make sense of what he was hearing. „Tommy, can you tell me anything else? Describe one of the men who brought you here or who is teaching you?“ The boy thought about it. „No,“ he said, „they all look basically the same and we don’t know any of the men who teach us.“ Then one of the other children, a blond boy who must have been no more than ten years old, spoke up: „Tommy, what about the Rooster?“ Tommy nodded. „That’s right, the Rooster is different from the others.“ Ewan looked at him questioningly and he continued. „We call him like that because he always dresses like a rooster. So colorful and weird. He always wears a scarf in bright colors, but the funniest thing about him is his top hat, which he doesn’t take off his head even when he’s indoors.”

December 17

Josephine

„One way to New Town,“ she requested and the coachman nodded. He tossed the hoof scraper that he had just used to clean the animals‘ shoes into the snow and turned up the collar of his waxed coat. Then he opened the door for her to get in. „Feicfidh me ar ball thú!“ he called to his colleagues at the carriage stand, a „Slán leat“ resounded back. „It might prove worthwhile to learn Irish,“ Josephine thought as she took a seat on the cushions – given the number of immigrants who now lived in the city and no doubt uttered most of their secrets in this unpronounceable language. But she could always leave that for later – right now she had other things on her mind.

Her spider’s web had presented her with a new catch that morning. A housemaid had tipped her off that several high-ranking guests had been invited to tea at her employer’s house – perhaps she would like to join in as a waitress? She wasn’t interested in spending an afternoon wearing an apron and carrying a tray, but rather in the information that Sir Richard Douglas was among the invited guests. The opportunity was favourable: an empty house – she had to seize the moment for further research.

At the door of the Douglas mansion, she again introduced herself as Evelyn Saunders. The butler who had let her in last time was enjoying an afternoon off due to his master’s absence, so she had to explain her request to an elderly housemaid. She had apparently just come from the kitchen, as the sleeves of her blouse were rolled up and she was wearing a stained apron. She looked insecure and Josephine took advantage of this. „I apologise for disturbing you, Madame,“ she said, and the inappropriately polite form of address visibly flattered the cook. „Just recently I was at an evening party in this house and Sir Richard showed us round the ground floor. I must have lost one of my earrings, because I missed it on the way back. Did you happen to find any jewellery like that bearing a sapphire?“ She pointed to her ear, on which a lone earring with a magnificent blue stone was swinging. Of course, the answer was „No“, because the counterpart remained safely in a secret compartment of her handbag, waiting to be presented as a „lucky find“ at the right moment. The woman shook her head. „Is there anyone else from the staff around that I could ask?“ Another shake of the head. Very good – that meant they were indeed alone. „Would it be very presumptuous of me to go and see for myself? You know, the jewellery is a gift from my husband. He gets jealous easily and if he notices that I’m missing an earring, he might start to think…” She was let in and after a few brief words explaining which room was where, the cook disappeared back into her domicile.

Careful not to provoke any suspicion, Josephine first went into the large hall where the evening party had taken place. The chairs and tables had been pushed together to form a large, long banquet table, and table linen had already been laid out for a dinner with many guests. She inspected the room carefully, but as she had suspected, in such a busy place no one would risk a guest unintentionally pressing a wall panel to reveal a secret compartment. In the hallway, Josephine turned directly to the library after assuring herself of the busy clatter of pots in the kitchen.

The room with its high shelves lay deserted in front of her. Dust danced in the dull winter light that fell through the high windows and the whole library was filled with the scent of old books, that mixture of tanned leather and weathered paper. She had already inspected the club’s secret room, so the desk was her first priority. The papers and documents on it were irrelevant and there was nothing of value in the drawers either. Josephine’s heart skipped a beat when she discovered a secret compartment under the tabletop – but it only contained faded photographs of a woman she didn’t recognize. She carefully put everything back as she had found it and then turned towards the hidden door.

Before she entered the corridor, she pulled the false shelf closed behind her – in case the cook did come to look, it bought her some time. Now she had to hurry. Fully concentrated, Josephine headed for the areas of the room that she had not yet examined during her first stay here. She was particularly interested in the furniture. She quickly ruled out the cupboard where she had been hiding – there was nothing here. Her fingers glided over the cool surface of the sideboard where the servants had prepared the drinks at the last meeting. With a practiced hand, she searched the back and bottom for a mechanism that would open a hidden compartment.

Suddenly she felt a slight vibration under her fingertips. There it was – a slight dent in the wood! She pressed it carefully and a flap on the side of the sideboard popped open, which had previously been invisible due to the rich decorations. A tingling sensation ran through her whole body as she opened the small compartment and discovered a series of documents. Time was working against her, she knew. She hurriedly combed through the papers and decided on a thin, black notebook labeled with the date of the current year on the front. She tucked it away deep between her undergarment and corset. She was just about to leave the room when her heart skipped a beat.

Footsteps and voices could be heard outside in the library. „She was looking for her jewelry,“ she heard the cook say. She looked around in panic. Would the linen cupboard make a good hiding place again? Should she crawl under the table? Or hide behind the door, take those coming in by surprise and simply run away? But before she could make a decision, the door swung open and someone entered the room.

December 16

Ewan

That impertinent person! Furious, he kicked a crate that had made the mistake of taking up too much space on the pavement. It must have been filled to the brim and therefore didn’t move an inch. Instead of the satisfying splintering of wood, all he heard was a crack and a sharp pain shot through his foot. Cursing and limping, he continued on his way. If he had broken his toes because of Josephine Fairchild, he would first print her large portrait on the front page of the Evening News and then set her house on fire, he thought, beside himself with rage.

His foot was still in pain when he reached Philip Rowe’s dockside office, which only fuelled his miserable mood. So he shoved the door open a little harder than he intended, causing a storm among the bells that were supposed to announce the arrival of a new customer. The secretary looked at him, startled, and Ewan took a deep breath to calm himself as he walked towards the counter. „Excuse me,“ he said, suddenly realising his battered appearance. „My name is Abraham Smithers. I have an appointment with Mr Rowe.“ That wasn’t true, but it was a tactic he’d used successfully many times before. He had made up the alias because there was no way he could go by his real name here. The woman glanced at her records. „What was your name – Smithereen?“ „Smithers,“ Ewan corrected. „I’m afraid there’s nothing written down here,“ she said regretfully after leafing through several pages. „We met by chance yesterday and he asked me to come round at this time today,“ he explained, „perhaps he forgot to tell you.“ She nodded sympathetically and sighed: „Yes, unfortunately that happens more often. You shouldn’t speak ill of your employer, but why don’t you tell me how I’m supposed to run a reliable secretariat this way?“ „I think you’re doing an excellent job,“ he said with a winning smile and she showed him the way to Rowe’s office, beaming with pride.

Philip Rowe was sitting behind a massive oak desk, busy reading some paperwork, when Ewan knocked and entered a moment later. „Good afternoon, Mr Rowe,“ he greeted politely. The man looked at him in surprise, but then pointed to the vacant chair in front of his desk. „Good afternoon, Sir! What can I do for you?“ Ewan sat down and tried to push his bad mood aside. Though he needed to concentrate fully, his thoughts kept drifting back to the frustrating events of the morning. „I’ve come to you with a few questions in the hope that you can help me,“ he said. Rowe laughed in a jovial manner. „Well, fortunately, today I’m in the mood to help you,“ he said. „Fire away.“ „I’ve come on behalf of the city,“ Ewan lied. „They’ve assigned me the task of enquiring into the disappearance of several children.“ The other man’s expression instantly turned sour. „And what on earth did you come to me for? Because of that heinous newspaper article, isn’t that right? Well, let me tell you something: it’s the work of ruthless dilettantes who don’t have enough truth and have to fill their greasy pages with lies instead.“ He lit a cigar, but his torrent of words wasn’t over yet. „You’re from the council, you say? I suppose they employ people who read this rubbish?”

With all his might, Ewan tried to remain calm. He shrugged, „Well, it’s a lead I’ve been requested to follow up. Your name is mentioned and it’s implied that you were last seen with Thomas Murphy.“ Rowe slammed his fist on the table. „Do I look like a common creep who associates with orphans?“ he thundered, „What are you insinuating here?“ „I’m not insinuating anything,“ Ewan replied, „I’d just like some answers.“ Rowe angrily stubbed out his cigar and leant back in his chair. Then he let his gaze wander over his opponent’s face and lingered on the wounds. Suddenly Ewan noticed a change in his expression, which vanished as quickly as it had come. Instead of anger, a sly grin spread across the man’s face, dripping with satisfaction.

„Please excuse my outburst,“ said Rowe, reaching for another cigar. „These are very emotional days for me. You have to understand, you’re not the first person to come to me.“ „Oh really?“ asked Ewan. „By this careless mention in a paper that the whole town reads, I’m constantly harassed. The matter has a simple explanation, but I’m not going to reveal it to every random fool. You’re from the City, you say? What was your name again?“ „City Clerk Smithers,“ Ewan replied as if shot from a pistol. He had made that up, as there was no way he could go by his real name. „City Clerk Smithers!“ exclaimed Rowe, “ Well, my dear fellow, I can come clean with you. The fact is, I have a brother who is hardly ever spoken of. Yes, you can read about my sisters‘ escapades in Town Topics every week, but my brother’s existence is a well-kept family secret. We were brought into the world together, but apparently I made his life so difficult in the womb that his mental deficiency soon became apparent. He’s not so incompetent that he can’t go on the occasional outing on his own and we’ve long suspected that he gets on with simple folk. That he chooses children as playmates is not surprising; after all, he’s always remained a child himself in his mind.“ Ewan nodded hesitantly. He was sure Rowe was lying to him. „And as your twin brother, he’s probably the spitting image of you?“ „Like two peas in a pod,“ laughed Rowe. „So now you can clearly see the strings which bind me: I can’t defend myself without compromising my family’s honour.“ What honour, thought Ewan, you’re a nouveau riche upstart whose family is only of public relevance because they flaunt their obscene wealth and whose sisters fling themselves from one embarrassing liaison to another.

Out loud he said: „Ah, that explains a lot, of course. Would it be possible to have a chat with your brother? Of course, this information is reserved for a select group of administrative staff.“ The businessman hesitated, then nodded. „Do you know Jacob’s Ladder just east of the railway station? There’s an excellent view of the train traffic from there. Kenneth loves the sight of the lights at dusk. You should find him there. I’ll pass on the message to the staff that you deserve all the help you can get.”

As he climbed the steps from Jacob’s Ladder to the top of Calton Hill, panting, he was sure that Rowe was leading him around by the nose. His twin brother, was he pulling his leg? But what else could he do? The steep staircase that had been carved into the volcanic rock lay abandoned before him. So he followed the path up to the hilltop. At least as far as the view was concerned, the man hadn’t been lying. It was phenomenal. Ewan wondered why he came here so rarely – but answered the question to himself straight away. There were fewer people up here to talk to for good stories. But there was a marvellous view over the city, with the mighty Castle Hill towering over the streets. Dusk had fallen and Ewan shivered. Now, where was this ominous brother? At the foot of the Dugald Stewart Monument with its Corinthian columns, only a few stray couples were wandering around.

Suddenly someone approached him. „Pleasant forenicht, Sur!“ Ewan turned around to find a freckled young man in a worn uniform jacket standing in front of him. Without another word, the lad pointed to a path that wound itself around the hilltop. „To Ryle Terrace,“ he said, as if that explained anything, and added: „Now git it movin.“ The reporter followed the boy hesitantly. He regretted leaving his walking stick at home, which could have been useful for self-defence. They walked in silence towards the sloping road that ran alongside London Road Gardens. Contrary to its pompous name, which suggested the highest circles of the aristocracy, „Whiskey Row“, as it was popularly known, was mainly inhabited by merchants who had settled here for the unobstructed view of the harbour and the incoming ships – and these indeed earned their money quite often with high-proof spirits from the northern distilleries.

Just before they left the grounds of Calton Hill and stepped out onto the street, the boy turned round. „Mah apologies, pal“ he said – and a strong pair of hands grabbed Ewan, a sack was placed over his head and blackness enveloped him.

December 15

Josephine

She was just finishing her breakfast when there was a knock at the door. Her housekeeper went to check on her request and came back with a slender man in a tweed coat. Josephine sighed, rose and poured a second cup of coffee. „Good morning, Miss Fairchild,“ said Ewan Cunningham, „will you allow me to sit down?“ She noticed immediately that his tone was quite sober. She put the cup down in front of him and examined his face closely. „I didn’t realise that being a journalist was such a dangerous profession,“ she said, pointing to the chair opposite her. He took a seat and now she could see the fresh bruises on his forehead and the wounded, swollen cheek more clearly. „Did you end up in a pub brawl or under a coach?”

The reporter took a sip and then looked at her with a serious expression on his face. „I’m not in a joking mood today. In fact, I don’t want to be here at all. But I don’t know which way to turn.“ He leant forwards a little and hinted at his face. “ Currently I’m researching a story and I think I got too close to someone.“ „The orphan thing?“ She’d read it in the paper. Ewan nodded. Oh dear heavens, the next person to pester her about it! Josephine reached for an apple that had been left on the table from breakfast and bit into it so she wouldn’t have to speak. The man continued without a second thought: „Believe me, you’re the last person in the whole of the British Isles I’d ask for help. But I suspect there’s more to it than that and you can be accused of many things, but not that you don’t know the soft underbelly of Edinburgh society inside out. Here’s the thing: I was ambushed in my office and given a message. Please take a look at this“ – and he pulled a folded-up piece of paper out of his pocket.

But Josephine had risen to her feet. „Well,“ she said, „I don’t think I can help you in any way.“ Ewan looked at her irritated: „You haven’t even read what it says!“ She made a dismissive gesture. „I don’t need to. To be honest, I remember our last encounter all too well. What did you call me again? Inconsiderate and … smug?“ Now was the time to make him realise his audacity and she would savour this sweet moment of vengeance.

A few hours later, she stepped off the tram, wrapped in a navy blue winter cape. She had decided to take the Morningside line, which connected the east end of Princes Street with the southern edge of the city. On boarding, she had noticed one of the shabby placards opposing the announced switch from horse-drawn carriages to electricity. The Bobbies regularly removed such notes, which proclaimed that travelling on the tram would make you infertile, feeble-minded or hysterical. She was sure that those for whom the city council wanted to set up this cheap means of transport would prefer to continue walking.

It had taken her almost an hour to get here. When they had left the old town in the direction of Marchmont, the fort-like sandstone buildings with their playful turrets and battlements were gleaming in the fading evening light. In Greenhill, the multi-storey buildings gave way to smaller villas, with parks and gardens in between. Despite the gathering darkness, Josephine could recognise numerous building sites. This was where the town was merging with the wealthy villages that favoured country life, and mansions were springing up like mushrooms. Even Morningside, the destination of her journey, was still a row of thatched cottages, a blacksmith’s forge and a sparse group of trees a hundred years ago. If anyone from that time was still alive, they would not recognise their village. The large farms and estates that had formed here due to the favourable location on the trade route to the north soon saw a better business in no longer cultivating parts of their land, but instead selling it to wealthy townspeople. Now everyone who could afford it was eagerly building their slice of paradise – or rather having it built, as Josephine doubted that any of these fine gentlemen would ever take on a job that made them sweat.

It was only a few metres from the station to the place Alastair Wallace had told her to meet. In their last conversation, he had asked her to be at the crossroads in the centre half an hour before six o’clock. As she walked towards it, she could already see a black coach waiting for her. He had offered to pick her up at her home, but she had elegantly avoided his offer. Under no circumstances could he know who she was or where she lived. Only a few steps separated them from the vehicle when the door opened and a beaming Alastair got out. He was wearing a black tippet today, which made him look like an undertaker. Courteously, he asked her to get in and the carriage rattled off. „It’s not far,“ he explained and the journey was indeed over after a few minutes. In a pointless gesture, he wiped the snow off the step of the carriage with his handkerchief before she stepped onto it – Josephine suppressed an eye roll and instead thanked him with a sheepish smile.

Their carriage had stopped in front of a magnificent country house that stood in solitude between a small wood and a stream. It was built like a castle, with stylised battlements and miniature towers. A gentle snowfall had begun and covered the meadows in front of the property with a white blanket, on which the light from behind the windows painted long yellow streaks. „Welcome to the Hermitage of Braid,“ Alastair announced, taking her arm and leading her up the three steps to the red front door. A well-dressed butler opened it just a few seconds after knocking, as if he had already been waiting behind the door. After she had been helped out of her coat and turned to her companion, she saw his eyes light up. Today she had opted for a salmon-coloured dress that left her shoulders uncovered. It wasn’t quite the late 18th century, but the highlight was the pearl necklace with a little bow that made her look like an Elizabeth Bennet or Emma Woodhouse. The dress was also decorated with embroidery and pearls that would sparkle beautifully in the candlelight – apparently they already did and did not fail to achieve the intended effect.

The dinner party that followed proved to be dull as ditchwater. From the pretentious landlord, an heir to the Gordon family, to his gawky wife and ill-behaved children, the other guests in particular made her want to drown herself in the nearby stream just to escape their bloated faces and irrelevant conversations. Against the backdrop of this chamber of horrors, Alastair underwent a miraculous transformation into a genuinely attractive conversationalist. After dinner, when he suggested showing her the historic dovecote along the park’s illuminated paths, she agreed almost too readily.

On the arm of her companion, she walked along a shovelled trail through the back part of the garden, which was laid out in terraces. Here the snow was heavier than in front of the house and the outlines of flowerbeds, hedges and small bushes could be made out under its thick layer. Here and there, a small tree wrapped in a burlap sack poked out of the white. Before they reached the dovecote, Alastair pointed out the 18th-century ice house, which provided lavish parties with chilled drinks, ice cream and sorbet even in the height of summer. „This is very fine company, Alastair,“ Josephine remarked gently as they walked. „Will you be able to count on their support when you make your move?“ Alastair shrugged his shoulders. „We’ll see, dear Genevieve, who turns out to be a loyal friend and who turns out to be a Judas.“ Josephine ventured forward. „My dear friend – call me a simple-minded woman who knows nothing about politics. But a man of your character must surely be able to secure the support of the masses without the help of third parties, simply because he has the unconditional will to do good!”

„Dearest Genevieve, you flatter me,“ Alastair returned and she could see a mixture of satisfaction and condescension on his face, „but high society plays by its own rules.“ „Come on dear, explain to me how the world works,“ she thought to herself. „Really?“ she said aloud, „I’ve always believed that sustainable wealth can only thrive on honest soil.“ Alastair examined her, but was met with only a coquettishly naïve blink. „You have no idea,“ he then said, „what intrigues are forged in the finest parlours in the city. Would you have thought, for example, that there is an organisation that operates in secret and has more influence than most people can imagine?“ Josephine put on a stunned face. „How extraordinarily fascinating! Can you tell me more about it or is the association that secret?”

Alastair looked around to see that no one had followed them from the house and lowered his voice. „It’s a secret Gentlemen’s Club that has operated in the shadows for generations. The members impact political decisions, economic matters and more. No one knows about it, but their influence extends far and wide.“ She acted as if she had never heard of it. „That almost sounds like a story from a novel, Alastair. Do you really think they could have an effect on your political career?“ He nodded gravely. „Oh, yes. Their influence is greater than people realise. They are pulling the strings in the background, guiding decisions and orchestrating power shifts. I have reason to believe that my political future depends gravely on their support.”

Don’t make a mistake now, don’t venture too far. „That sounds very dangerous!“, she exclaimed. „However, if you do have their support, it sounds like you could really achieve quite something. Are you planning to join them?“ Alastair hesitated for a moment before answering. „That’s already happened. But I’ll let you in on a secret today, my faithful lady: I plan to use their power to achieve my goals. Once I am Lord Provost, I will turn things around so that her secrets come to light. The club will crumble and I will free the city from their invisible grip.“ Josephine grabbed his arm in a dramatic gesture: „A daring plan, Alastair – I’m worried about you! Do you have any confidants you can count on?“ The man gave her a smile. „Only you so far, my love. But I must assure myself of your absolute discretion. You know, the best plans are those that flourish in the dark.”

December 14

Ewan

„Have you read the Evening News today?“ Ewan slowed down. He would’ve loved to overhear this conversation. To avoid being noticed as an eavesdropper, he pretended to look at the display in a nearby shop window.

„Of course I did,“ replied the other man. Wrapped in thick, black fur coats, the two coachmen stood next to their vehicles. The one addressed smoked a cigarette and blew little clouds into the cold air: „What are you getting at?“ „What do you think I’m getting at, you git,“ grunted the other man. He was grooming one of his Belgian Draughts. „I’m talking about the lead story on the orphans. They’re disappearing at every turn. What kind of shenanigans could be behind that, I wonder?“ His dialogue partner threw his smoked cigarette into the snow. “ So who cares about a few orphans? Fewer mouths to feed and more money for honest labourers, that’s my thinking.“ The first man looked at him for a long time, then shook his head contemptuously. „Sometimes I wonder why I’m even talking to you – you’ve got absolutely nothing between your ears.“ He bent down to brush the clumps of snow from the horse’s legs and grumbled: „What’s he reading the paper for, what a complete waste…“ The other just laughed and lit another cigarette.

Apparently the conversation was over, so Ewan continued on his way without attracting attention. He was on his way to the newsroom and wanted to get something to eat before the late shift. On the World’s End blackboard, a Brown Windsor Soup was advertised as the dish of the day, which he found appealing and decided to have dinner here. As he left the pub, a cold wind caught him and tugged at his coat. Darkness had already fallen, although it wasn’t even five o’clock yet, and the gas lanterns bathed the street in a faint yellow light. Suddenly he felt uneasy. Without thinking about it, he grabbed the back of his neck as if to ward off a gaze that had been fixed on him. He turned to look, but the street behind him was empty.

A shadow flitted across the pavement in front of him and Ewan gasped in shock – and laughed at himself. It was just a cat. The alleyway lay silent and deserted before him again, only in the distance he could see a few figures hurrying through the twilight. There! Those were footsteps behind him! He had definitely heard the crunching of loose stones under the soles of someone’s shoes. Ewan quickened his pace, hurried, almost ran, until he reached the doorway of the editorial building. There he turned back, but again there was no one to be seen.

Later, as he sat at his desk with a pipe and a pot of coffee, he felt silly. Perhaps the ale he’d had for dinner had clouded his senses. Yes, it was possible, because he rarely drank, and if he did, it wasn’t strong alcohol. But the footsteps … he was so sure he had heard them clearly behind him. Ewan pushed the thought away with an effort. Instead of driving himself crazy over an imaginary pursuer, he’d better get to work. This paid the roof over his head and meal in his belly. He took on a particularly tricky piece of research he had done some time ago. Still, he hadn’t found a good starting point for the article. Soon his mind jumped at the challenge and when his colleague exclaimed „I’m off then“ and left the newsroom, he was up to his nose in his notes and barely noticed the man. There was darkness outside the office window and when he tried to look out, he only saw his own pale face in the reflection of the pane.

A little later – he couldn’t say how much – the sound of the front door caught his attention. „Sam, is that you?“ he called out to his colleague, who had apparently forgotten something he had come back for. Silence was the answer. Ewan looked up from his papers in astonishment – and received a heavy blow to the head.

When he woke up again, his vision was blurred. Three people were standing around him, he and his chair had been dragged away from his desk to the centre of the room. A fourth person was searching through the documents on the table. „There’s nothing here,“ he heard someone say dully. „Then let’s get out of here,“ said another, „he looks like he’s learnt his lesson.“ A stocky figure walked towards him and came close to him. Ewan tried to open his eyelids more, but they were thick and painful. Still, he saw with horror that the person now almost touching his face was a boy of less than twelve. „I think there’s more to it,“ the boy said, and a fist hit Ewan in the face, knocking him out of his senses.

Hours later, as it was getting light, Ewan was woken by someone shaking him by the shoulders. „Mr Cunningham! Mr Cunningham!“ It was one of the paperboys who came every morning to pick up last night’s paper for the early risers. „I … I can’t,“ Ewan moaned. The boy supported him as he sat up in his chair. „Mr Cunningham, sir … I’ll get a doctor right away,“ he then said and ran out. Ewan carefully felt his face and head. This could well be a painful and unsightly recovery. When his gaze fell on the desk, his breath caught in his throat. Not only was there an unholy mess of papers, exercise books and notes, but last night’s visitor had left him a note. Someone had smeared three words in large letters across the tabletop in black poster paint.

Ewan groaned and stood up to get a better look. It read: „nihil sine causa“.

December 13

Josephine

The rain had not stopped pouring down over the city since morning. A grey blanket of cloud hung over Edinburgh, making it seem as if the sun had not risen at all. Josephine looked out of the window and watched the water, running ceaselessly in rivulets along the pane and collecting in wide puddles on the streets. In some places it was already flooding the kerb. She watched with amusement as the fine gentlemen and ladies tried to reach the shops on the winding streets of the old town without getting their feet wet.

She, on the other hand, was sitting in the warmth and enjoying her afternoon tea. This little café was just the place to be on an overcast day like this. All in all, Josephine was very pleased with herself. She had spent the morning tending to her ’spider’s web‘, as she quietly called it. This consisted of around fifty maids, waiters, servants, shoeshine boys, barmaids and housekeepers from the various better-off households and districts of the city. Josephine had carefully selected every single person and had planned the contact well in advance. Some were easier to convince, others needed a little motivation. In some households, she first had to work for a few months herself to gain the trust of the other employees. With others, only a simple bribe would do – but she succeeded with all of them. Now her net stretched across the whole city and offered the opportunity to make promising catches even in the most private areas.

A waiter brought her a platter of appetisers, including small sandwiches with egg and anchovies, several slices of seed cake, some fruit and scones with clotted cream and strawberry jam. Josephine took a large sip of tea and immediately ordered another pot. Then she turned her attention to the food while her thoughts drifted back to the events of the morning.