The archive of the Cathedral School was housed in a building half carved into the rock. Surprised, Eva let her gaze wander across the winding rib vault that now stretched before them. From the central aisle branched countless narrow paths between low wooden shelves, and brass plaques on the ceiling showed the way. Everything lay in the yellow-red glow of oil lamps, and the velvet-covered reading chairs by each small worktable looked so inviting that Eva longed to sink into one. Then the heavy door slammed shut behind them, and the outer world fell silent at once. No more howling mountain wind—only stillness: dry, ancient, of that peculiar kind that stuffs itself into one’s ears like wool. The air smelled of dust, of cold stone, of paper and ink.

Corwin seemed changed in this place—less the master navigator he was known to be, and more the student he had once been. His hand glided almost reverently along the leather spines of the books as he led them down the aisle, quietly commenting on the plaques. “Engineering” – “Astrophysics,” “Meteorology – oh, they’ve rearranged things! That used to be nearer to Cartography.”

“What are we looking for?” Eva asked.

“I’d say we start with a few old current charts of Goldendale,” he replied, “but for that, we’ll need the historical section. The new books won’t help.”

They delved deeper into the archive. Eva noticed gaps in the shelves—sections neatly labeled, but conspicuously empty.

“The students seem diligent,” she remarked, gesturing toward the vacant spaces.

“No, the materials can’t leave this wing,” Corwin explained. “Perhaps some volumes are at the restorer’s.”

On they went, past seemingly endless rows of shelves until they reached a low door. Carved into the stone lintel above it were the words Historical Section V–VIII.

“Here,” said Corwin softly. “Ready for the catacombs?”

They were most certainly not ready for the catacombs—though the incident in the burial chambers of Heaven’s Rest lay years behind them. But they couldn’t tell him that, so Finn merely said, “After you, Master.”

Corwin pushed open the door. A steep stairway descended into the depths, and there was no railing to hold on to. At least I’m not claustrophobic, thought Eva. The vault hung low, oppressive. Corwin walked ahead in solemn steps, with the pathos of a church sexton leading his flock through a cherished chapel. The brass signs down here were tarnished, their inscriptions almost illegible.

At last, they reached the section they sought. Corwin planted himself before the shelves, hands on hips, murmuring as his eyes moved over the bindings. One by one he drew out massive tomes and unloaded them—without ceremony—into Eva’s bewildered arms, adding brief annotations each time:

“Mayr’s Guide to the Doctrine of Currents—pioneering in its day, pioneering, I tell you!”

“The Alfvén Theorem Reconsidered—worth a revisit …”

“Fluid Dynamics of the Mid-Cloud Isles—also rather essential …”

Then he heaved out a thick, leather-bound volume whose spine was almost illegible. “This one’s at least a century old. You might not recognize it, but it’s the Physica insularum nubicum—back before it was split into the three parts we use today.”

Meanwhile Finn had stopped at another shelf, pointing to a large-format book with pages yellowed at the edges.

“What about this—Catalogue of Air Movements over the High Isles? That might help, too.”

Eva freed a hand and opened the topmost book on her stack. It was wrapped in heavy leather, and on the first page, written in ornate script, stood:

“A Compendium of the Knowen Ayre- and Streame‑Shapes, with especiall Regard unto the Wind‑Wonders over the Isle of Goldendale, inquired and sett downe by Doctor of Physick Aldwyn Vesper, Anno Domini 1847.”

Eva drew in a sharp breath. “1847—that’s ages ago. Is any of this still relevant?”

Corwin and Finn exchanged a look.

“Eva,” said Corwin, “you’re a splendid pilot and a magnificent Grandmaster—but this is our domain—or rather, my domain.”

“Very modest,” Finn laughed. “What do I know? I’m only a weather balloon.”

Together they hauled their findings to a small table surrounded by a herd of velvet chairs. Eva arranged the tomes before the men and dropped, relieved, into one of the plush seats while Corwin drew an oil lamp closer.

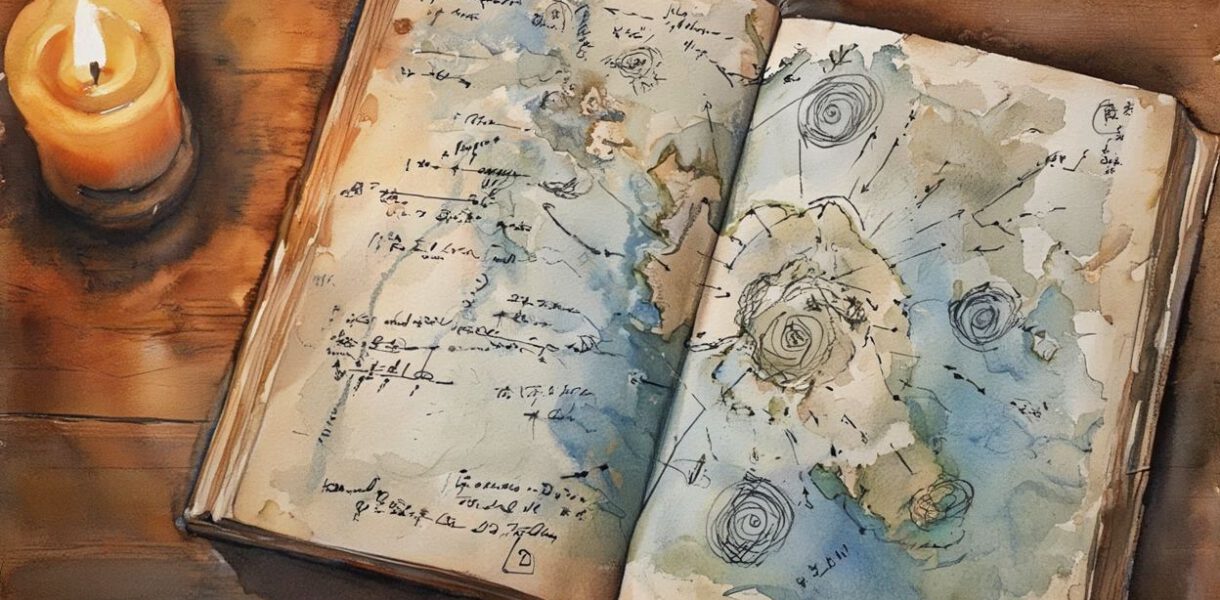

The first pages were hard to read—the ink faded, margins littered with later annotations. Then Finn stumbled on a passage illuminated with intricate drawings: long arrows showing wind directions, whorls swirling about a stylized cloud‑isle.

“Here,” he said. “This looks interesting—it’s a description of the conditions over northern Goldendale.”

Corwin leaned closer, tapping one of the arrows. “Indeed. These show vertical circulation patterns. Vesper distinguished between the primary wind field—the large overarching currents—and the secondary flow structures.”

“The induced current,” Finn murmured, pointing at a penciled note. “Someone added that later—fifty years ago at most.”

Eva followed the line he indicated. The passage described a phenomenon where, under certain conditions—when the main flow met an obstacle or irregularity of terrain—additional vortex zones would form. Whirls that did not weaken the primary stream but strengthened it instead. Eva leaned back, lost. The men’s technical chatter blurred into a pleasant hum.

Suddenly Finn all but jumped up. “It’s like a fountain—when you force water through an opening, it speeds up, but also becomes more focused!”

“Exactly,” said Corwin. “The good old current theory!”

He turned a page, searching, until he found one marked with fresh numbers. “Vesper noted the wind density—and look here.” His finger traced a handwritten margin. “Someone updated it with modern measurements.”

Eva stood and leaned over their shoulders. “I don’t understand a word.”

“It’s simple,” Corwin replied with a mischievous grin. “The natural current distribution over Goldendale is spatially inhomogeneous—that is, local wind speed and momentum density vary sig—ow!”

“Shut it,” Eva said, retracting the hand she’d just used to rap his head.

“What our Master of Water‑Heads meant,” Finn mediated, “is that the wind over Goldendale isn’t equally strong everywhere.”

Corwin had already opened another book. “This one’s older, and it says the very same thing. Which tells us: the phenomenon itself is ancient—primeval, even.”

Like the story of the Rye‑Wolf, Eva thought but didn’t dare say aloud. The wolf walks the corn, whispered the old man in her memory. Yes—that must be it: the scientific explanation of a centuries‑old Goldendale legend. No wolf at all, merely a curious wind.

Finn frowned slightly. “But what I felt on Goldendale—that wind wasn’t normal. Nowhere else have I sensed anything like it.” “That,” Corwin said, “is the great mystery. There’s a record of an anomalously strong current—clear as day—but not nearly as powerful as what you felt and what we later measured.”

Eva’s mind leapt to the warehouse. The device. Those interlocked metal rods. It created wind. But why create more wind when you already had a strong one? She voiced the thought aloud.

Corwin looked at her—and in his eyes flashed sudden comprehension.

“The anomalous wind was always there,” he said, “but that apparatus amplifies it. Don’t you see what that means? If someone can strengthen a stream that powerful, they can also control where it goes. And if that someone belongs to the League — everything makes sense. Everything!”

He shot to his feet in excitement. “Imagine it—delivery times shortened, transport costs cut, fuel saved—all by tuning the natural airflow.”

“That would be a pretty good reason,” Eva mused.

“Yes,” Corwin went on, “except for one catch: meddle too much with the wind, and soon… the weather itself begins to change.”