As the swiftship Aquila Celeris set its course eastward, the mood aboard had shifted. The bustle of the past days had given way to concentrated silence. Eva stood by the railing, lost in her thoughts. What had happened at the place of execution wouldn’t leave her mind. Airis… she pushed the thought away. Airis was too valuable for the pirates to harm her. And yet the worry lingered — her constant companion, subtle and nagging like a stone inside a shoe. Time to refocus on the mission at hand. Eva looked down at the vast expanse of sky, clear and translucent today, like spring water. In the distance, individual islands took shape, and far, far below them one could glimpse the land through a thin veil of clouds — distant and unreal, like a parallel world. The dwellers of the cloud isles simply called it the ground.

There had been times when people tried to bring those two worlds closer together. Early colonization attempts from below had all failed miserably — undone by unpredictable storms, the sheer technical challenge, and the realization that the human body could only adapt so far to two such different realms. Those who lived long upon the cloud isles grew sensitive to the dense air and altered radiation of the ground; conversely, ground dwellers often suffered from vertigo, disorientation, and months of fatigue when they lingered above for too long. Real exchange or even migration between worlds was barely possible.

Then there were the old tales. For generations, children of the isles had been told of the cursed depths: of giants who roamed below, of monsters lurking in the storms, and of eternal darkness beneath the clouds. Stories meant as both warning and lesson — because falling from a cloud isle was no metaphor, but a very real danger. Trade with the ground had never truly taken hold. What was technically daunting and socially taboo simply wasn’t worth the effort. The isles prided themselves on self-sufficiency, fiercely guarding their independence. The only regular contact came through fleeting visits: the wealthy who could afford a cruise through the skies, guided stays of a few days — enough to marvel, never enough to belong. Must be strange, Eva thought, to live that way, with a whole world floating above your head.

Behind her, a rustle of paper tore her from her thoughts. Corwin Dahlberg had bent over the chart table, spreading several sketches he had drawn — rushed, but precise: cross-sections, arrows, margin notes — the device from the storehouse dismantled, at least on paper. Corwin spoke softly, more to himself than to anyone else, absently running a hand over his clean-shaven chin.

“I understand the mechanics,” he muttered. “But the place… why that place?”

“The current pattern there is highly unusual,” someone answered. “I doubt it’s a coincidence.” A young man leaned against a porthole with folded arms, gazing outside. He wore no Order uniform but a long, elegant coat bearing the emblem of the Navigator’s Guild — specialists in storm zones. His hair had grown quite long since they had last seen each other, Eva thought, watching Finn with a faint smile. His presence filled her with quiet, unexpected joy. Her old friend had only been at headquarters by chance when the summons came — one of his habitual detours to see Eva, trade new wind charts with Corwin over coffee, eat badly and sleep even worse for a few nights. Sixten had summoned Corwin to Goldendale without realizing he would gain not one but two experts on fluid dynamics.

Upon their arrival on the grain isle, Eva had led both men straight to the storehouse containing the device. Yet before they even reached it, her old friend had stopped dead in the middle of the shingle fields. “Something’s off here,” he’d said. When Eva pressed him, he’d replied curtly that something about the air currents over the field felt wrong, though he couldn’t tell what. After she demonstrated how the device worked, Corwin had eagerly talked without pause while Finn withdrew into thoughtful silence. That dynamic hadn’t changed since: Corwin had spent days studying, sketching, and practically dissecting the machine, while Finn had been mostly absent — borrowing a horse and, at Eva’s insistence, taking along a Conclave guard for company. For what purpose, he never said. Not being a member of the Order, he owed no one an explanation.

Eva meanwhile had buried herself in reports. One squad from the Order had returned to the harbor district to escort Harbormaster Kardo Elsen — still shaken and hiding in the merchants’ guild storehouse — to safety, bringing her the port authority’s logbook along the way. Combined with the current harvest records of the Goldendale administration, a mountain of paperwork now lay before her. Yet nothing seemed to fit, and she wasn’t even sure what she was looking for. She felt as if she were searching for an object in a haystack without knowing whether it was even a needle.

“This is definitely not a natural current,” said Finn, pointing to a blue line on Corwin’s chart. “And it runs right over the fields by the storehouse. I rode along it for a good stretch the other day. The boundary’s far too sharp.”

Eva stepped closer. “You mean the wind’s being manipulated?”

“I can’t prove it, of course,” Finn replied. “I can only tell you what I feel.”

“I think we’ve got our proof right here,” said Corwin, pulling a handwritten list from the clutter. “The wind readings we measured don’t match the official charts. But they do match what you sense. You’ll have to tell me sometime how you learned that trick.”

Eva and Finn exchanged a glance. No — the story of the Heart of the Sky was best kept between them.

“I’m certain we’ll find answers in Eldbridge,” Finn said quickly.

Corwin nodded. “The cathedral school’s library is phenomenally organized, and I still have some friends among the archivists. It shouldn’t take long to find what we need.”

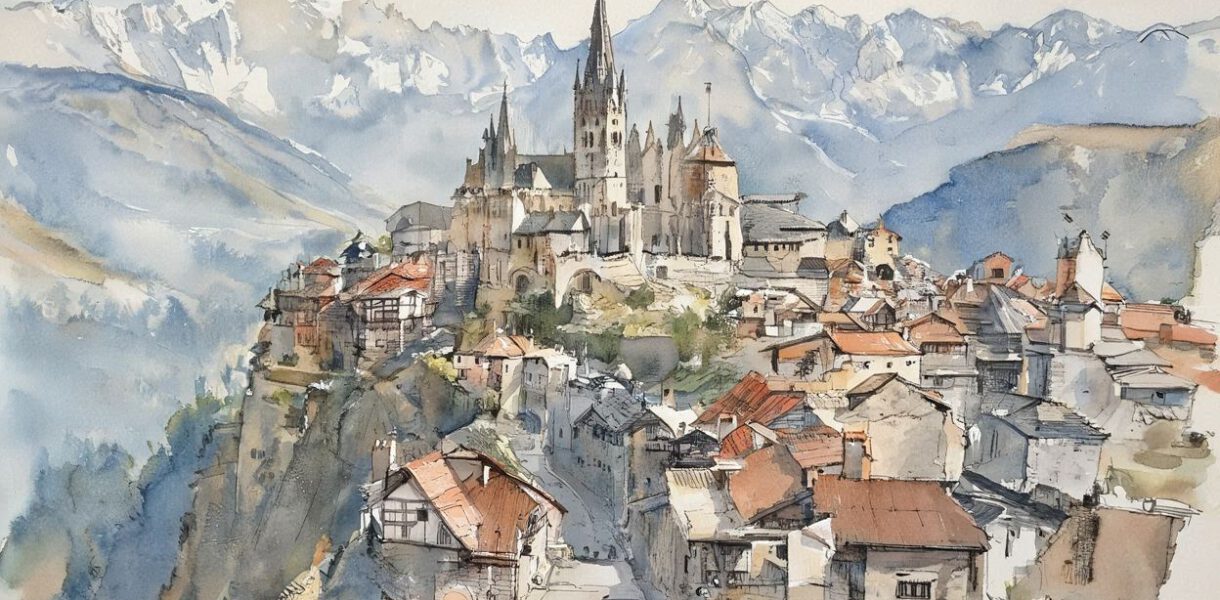

Hours later, the Aquila Celeris broke through the upper cloud layer, revealing the magnificent panorama of Thur. The isle was nothing like the gentle fields of Goldendale — it was a single, jagged mountain range suspended in air, a colossal rock adrift among the skies. Sharp ridges carved through the landscape, while deep chasms gaped between them, their shadows impenetrable even in daylight. At many points the stone dropped sheer into bottomless space — that hollow void giving the cloud isles their dizzying character. Snow blanketed the higher slopes, collected in hollows and ravines; below stretched gray cliffs, pine forests, and alpine meadows. Eva stepped closer to the railing. The air seemed even clearer and thinner here than usual at this altitude. Thur was one of the higher cloud isles. After they had crossed a peak, the city of Eldbridge came into view below.

The city sat upon a narrow rocky spur, as if deliberately placed just so — high enough to be seen, yet defended by the rugged terrain around it. From above, Eldbridge looked compact but strikingly orderly. Narrow lanes wound between whitewashed houses pressed close together, their steep roofs heavy with shingles and deep eaves to fend off snow and wind. Wooden balconies jutted over precipices, and many façades were bright with painted flowers or beasts.

Above it all rose the cathedral. Its massive body dominated the city’s highest point. Broad pillars clasped the rock, as if anchoring the church itself to the isle. The tower thrust high into the sky, its spire bright against the blue, while its tall windows mirrored the light. On a small terrace near the church, the Aquila finally landed.

After passing flight control, Corwin led them across the campus of the State Cathedral School. They crossed several adjoining courtyards, arcades, and slender towers — less monumental than the cathedral yet far busier. Students in dark coats and thick scarves hurried across the cobblestones, carrying papers, instruments, or heavy books. Between them moved older scholars, deep in discussion, as if they had long forgotten the world beyond the cloisters.

“Nothing’s changed here,” Corwin murmured with faint satisfaction. “Except maybe everyone’s moving faster now. Or I’ve slowed down — that might be it.” Eva cast him a teasing glance.

They passed a courtyard centered on a stone fountain. As they crossed it, a young man stopped short, staring at Corwin as though seeing a ghost. “By Zephyros… what are you doing here?”

Corwin blinked, then grinned. “Hannes? I could ask you the same! Got yourself registered here for good?”

The man laughed. “Something like that. I’m with the Department of Physics now. But you — you’ve got nerve, coming back here. I must say, I’m impressed.” His gaze slid to Eva and Finn. “I hope you realize you’re traveling with the Map Mutilator of Eldbridge?”

Eva raised an eyebrow. “The what?”

“An unfortunate title,” Corwin admitted, “stemming from a youthful indiscretion involving a very old map.”

“He cut it up,” Hannes clarified.

“And then pieced it back together — improved it, in fact. The professor of historical cartography didn’t speak to him for three days.”

“Only three days?” said a voice.

An elderly woman with snow-white hair stepped out from beneath the arcade. Leaning on a cane, she looked Corwin up and down, clicking her tongue in disapproval.

“Dahlberg. Merciful heavens above — tell me it is not so! You have joined the Conclave?”

Corwin sighed. “Professor. How lovely to see you.”

“I should dearly like to reciprocate that sentiment,” she replied, “but alas — I cannot. It is a catastrophe of intellect! Once a man of uncommon comprehension, possessed of a sensitivity to the subtlest motions of air such as few minds have ever conceived — and now reduced to tinkering about in the clouds like some overpaid sky-coachman! You have abandoned the noble art of aerological reasoning and exchanged it for the vulgar sport of… navigation!” She raised a trembling hand in theatrical despair. “It is as though Aristotle had run away to join the air circus!”

She cast a brief, deeply suspicious glance at Eva.

“Too much open air, Mr. Dahlberg, inevitably leads to the evaporation of mental substance. The contemplative mind, if it is to remain sound, must—how shall I put it—ferment in peace, not flap about like a weather vane!”

“Have you seen the man?” Finn said calmly. “That belly’s the result of too much peace.”

Corwin burst into laughter.

The scholar sniffed in disdain. “Navigator?”

“Obviously,” said Finn, gesturing to his guild badge.

“Ah! A lamentable hybrid of scholar and daredevil — half philosopher, half weather balloon! Very well.” She drew herself up, clutching her cane like a scepter. “So these are your associates now, Dahlberg. It is said the gravity of a mind may be judged by the company it orbits — and I see your trajectory has fallen considerably from the academic heavens.”

She turned away with a grand sigh. “You know the way to the archives, I presume. And hear me well: should you once more lacerate, annotate, or—heaven forfend—attempt to improve any of my maps, I shall not hesitate to file the necessary writ of expulsion, have you dragged to the docking bay, and personally see you flung from the island in the name of academic hygiene!”

“No promises,” said Corwin with an irrepressible grin, which she did not return.

“Ha! Just as I feared,” she muttered, sweeping off with all the offended dignity of a thundercloud in search of a better storm.

They left the professor behind, shaking their heads, and went on their way.

„Daredevil? Weather balloon? What in the heavens just happened?“ Finn was consternated. Eva shot Corwin a sidelong glance. “Map mutilator?”

“It was a one-time thing,” he defended himself. “My version was far better. I think that’s what truly bothers her — not the ruined map.”

Finn chuckled softly. “Sounds like you enjoyed your studies.”

“I did,” Corwin admitted with a laugh. “Maybe a bit too much.”

At last they stopped before a heavy door of dark wood, the words Archive of the Cathedral School carved in stone above it. Corwin rested his hand on the handle. “If there’s anywhere we’ll learn how to control the winds,” he said, “it’s here.”